The role of User Generated Content (UGC) in marketing strategies is on the rise. Brands have realized how valuable it is to tell their story and advertise their products using genuine images shared on social media by real-life customers, either in place of – or in addition to – traditional ads staged with models.

With this shift has come a host of legal questions: when is it ok to use an image shared to social media? When does a brand need to get permission to use the photo? And from whom? The photographer, the subject in the photo, and the network where the content was posted all potentially have a legal claim to content that brands might use for advertising or other monetary gain. It’s a new legal domain – and the legal teams of large companies are often wary of “User Generated Creative.” The good news is, it’s not impossible to navigate, it doesn’t need to be confusing, and it can be done safely.

When do you need to get the rights to User Generated Content?

There are a couple key questions marketing managers or legal teams can ask themselves, to understand when and who they need to get permission from. The two most important questions are:

- Will we profit from using this image? / Does this qualify as an advertisement?

- Are we taking the content out of the protections of the network’s terms of service?

There is a myth that once content is posted to social media, it is free to use by anyone. This is not true – thanks to copyright law, the photographer still retains the legal rights to these images. This was supported by the ruling of a judge in the 2013 U.S. District Court case: Agence France Presse v. Morel. Morel, a professional photographer, sued the news wire for publishing his photograph without his permission and won. The news wire unsuccessfully argued that by uploading the images to Twitter, Morel had indirectly given them permission to distribute and reproduce his photo. If you want to use a photo, you need to get permission from the photographer.

The exception to this rule, is if you keep the content on network.

Every social network, from Instagram to Youtube, has users sign an agreement that gives the social network and its partners a license to share and display public photos. For example, in the case of AFP v. Morel, the judge cited the twitter Terms of Service (TOS), which he stated, “provides that users retain their rights to the content they post – with the exception of the license granted to Twitter and its partners.”

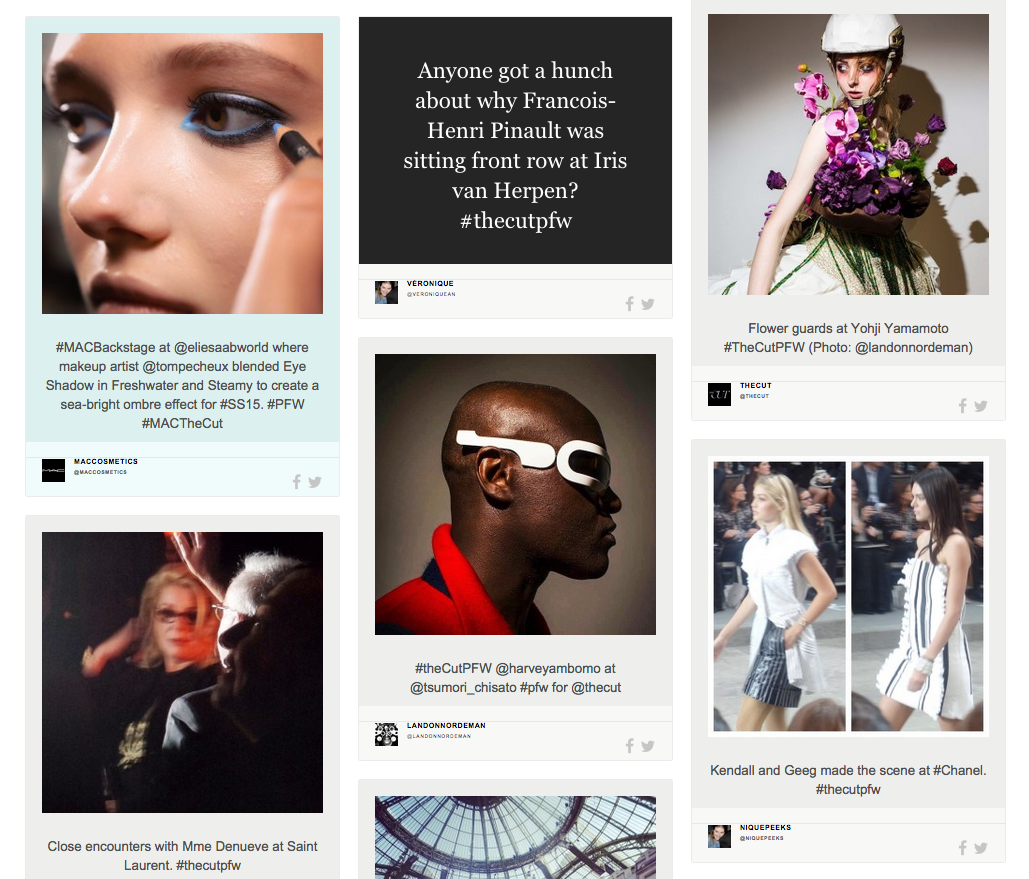

These partners include social media aggregation and display services like TINT, who legally pull the content through the networks’ APIs, and comply with their requirements for partnership – for example, including the twitter icon on all twitter posts. So it’s possible to display social media content on your own website or at an event without technically removing the content from the protection of the network’s TOS, provided you do so through a partner of the network.

However, most networks do not allow brands to profit from their content or use their content for advertising purposes, while still under protection of their TOS. In order to avoid owing the network a cut of your revenue from advertising, you will need to get all the proper permissions that you would for any type of advertising – this includes the photographer (to protect your brand from copyright law) and possibly the subjects of the photograph (to protect your brand from statutory publicity rights). The larger the potential monetary gain from the advertising campaign, the more careful you will want to be about complying with publicity statutes.

Whether you need to get permission from the photographer and subjects depends on whether you are still protected by the network TOS. This depends on how closely the User Generated Content is associated with the advertising. There are three main types:

Types of Advertising with User-Generated Content

Adjacent = Good to Go

Adjacent advertising means that the user-generated content and the ad appear on the same page, but clearly separated from one another. For example, a webpage with both a social hub with a banner ad. For the most part, you can do this safely without specific permission from the poster or subject, provided you follow the above guidelines to make sure you are still protected by the network TOS.

Content as Advertisement = Definitely Need Permission

If you change the content to become an ad itself – for example, putting text over the image, or including it on a billboard – you must follow all the necessary guidelines for traditional ad creative.

Whether you’re nervous about publicity rights or the networks, you should seek content rights to the image before using it directly as advertising.

Inline = Gray Area

Increasingly popular, is the effective marketing method of mixing advertisements or “click to buy” buttons with social posts. The posts are not advertisements in themselves, but unlike banner ads, the ads are disguised to look similar to the posts. An argument could be made that this is using the UGC effectively as advertisement. As we mentioned earlier – this is a new field, and there isn’t a concrete answer yet. It’s a gray legal area, and brands are deciding on an individual basis how carefully they need to protect themselves. Getting rights to the image directly from the photographer is a great way to play it safe and protect your brand.

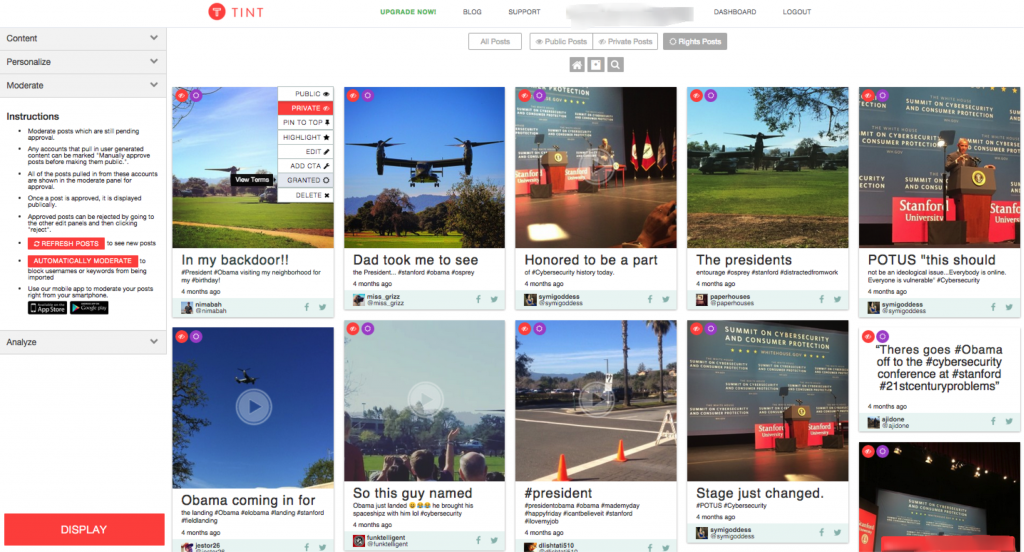

In this example of inline advertising, from NYMag’s TheCut, the “post” in the upper-left-corner is an ad for Mac Cosmetics, while the rest of the posts are from their reporters in the field at NY Fashion Week.

How do you get permission?

There are a number of ways that brands can seek permission from the photographer in the new social media landscape. Some make a distinction between “Implied Consent” and “Explicit Consent.”

Implied Consent v. Explicit Consent

Implied Consent

Implied consent means that a brand can reasonably assume that the person who uploaded a photo intended for the company to use it, and was aware of the company’s intentions for the photo. The most common way that this happens is through the use of a specific hashtag, which can convincingly be argued would only be used by consumers aware of the company’s campaign. For example, #ShareaCoke.

These campaigns are marketed with terms and conditions that describe the brand’s intended uses for the photo. Lonely Planet’s #BestPlacetoBeToday campaign is a great example of a hashtag campaign with terms and conditions attached. Essentially, you can argue that this is “commissioned” rather than “native” content.

However, as we’ve outlined above, if you are displaying the content through a network partner and using it for non-monetary purposes, you don’t even need implied consent – you could display #Cars (an example of native, not commissioned, content) and not worry. Therefore, for campaigns where you do need consent (ie, where the content is being used as advertising), it is likely worth your time and effort to procure explicit consent.

Explicit Consent:

Explicit consent means you have asked for and received specific permission to use the content.

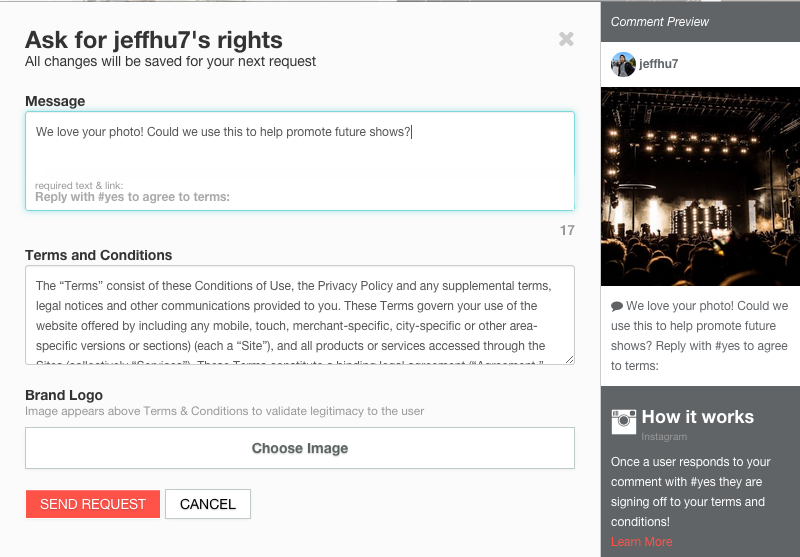

Due to the increasing need from brands to get the proper permissions to use UGC in advertising, or in other uses beyond the protection of the network TOS, social display tools like TINT have expanded to included a Content Rights Solution for social content. These services allow you to discover content relating to your brand, request the proper permissions from the author of the image via social media, and track which images you have the rights to. While services like TINT facilitate the permissions, the legal language is still determined by the brand. The agreement can include a certification from the author of the post that they own the image, and that they have permission from the subject of the photograph.

A quick review:

Good to Go

– API partners: Using a service that displays social content in a way that complies with the networks’ rules allows you to display content on your campaign landing page without worrying about permissions, provided you are not turning the content into an advertisement. We recommend you ask any social display service you use if they are partnered with the social networks.

Need Permission

-Any use outside the protection of the network’s TOS (ie not through a network display partner)

-Advertising campaigns, potential for monetary gain, modifying the content so that it explicitly sells something

Gray Area

-Implied Consent aka “Commissioned” Artwork: collecting UGC through a specific, branded hashtag, which implies the user has read the brand’s terms for participating in the contest / campaign.

-Inline advertisements- displaying the UGC unmodified (and through a network partner) mixed with advertisements disguised to look similar to posts.

If you are interested in repurposing social media UGC for your campaign, marketing collateral, media news, or advertisement and need a solution, read more about TINT UGC Rights Management or Request a Demo from TINT.

Disclaimer: No information accessible on this page or through this website should be construed as legal advice, legal opinion, an endorsement with respect to any matter, or a solicitation for legal business. You should not rely on any such information as legal advice without actually consulting with legal counsel.